The Old “Color Line”

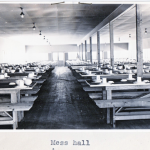

If you had looked in the mess hall on Wake Island at dinner time on any given day in 1941, you would have seen a sea of white faces. Some bore dark tans from hours in the tropical sun, but most were Caucasian except for a few Pacific Islanders and a couple dozen Chinese Americans. The “color line” was a wall against equal opportunity: preferential hiring, segregation of workers, and ethnic biases were entrenched in the construction camps and defense factories in the prewar period.

If you had looked in the mess hall on Wake Island at dinner time on any given day in 1941, you would have seen a sea of white faces. Some bore dark tans from hours in the tropical sun, but most were Caucasian except for a few Pacific Islanders and a couple dozen Chinese Americans. The “color line” was a wall against equal opportunity: preferential hiring, segregation of workers, and ethnic biases were entrenched in the construction camps and defense factories in the prewar period.

In June 1941, A. Philip Randolph, prominent African American labor leader and social activist, pressured the federal government to address the exclusion of black workers from defense jobs and threatened a mass march on Washington D.C. to protest discrimination. Randolph called the march off when President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802, which banned discrimination on the basis of “race, creed, color, or national origin” in defense industries. (Randolph later pressed for abolition of racial segregation in the military, which was accomplished in 1948 with Truman’s Executive Order 9981. It was Randolph who organized the historic civil rights March on Washington in August 1963 at which Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.) However, in spite of Roosevelt’s Executive Order, the hiring offices of the Contractors Pacific Naval Air Bases (CPNAB) forwarded no African Americans from the mainland to work on Wake or the other outlying island projects underway before the Second World War.

Initially CPNAB hired Honolulu men by the hundreds for the early projects on Oahu. Pacific Islanders found jobs as harbor and dock workers and experienced divers set dynamite charges to blast coral. The Oahu population also included residents of Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese ethnicity and many were hired for both skilled and unskilled labor. Chinese Americans from Honolulu and later from San Francisco were hired chiefly as mess men and laundry workers on Wake and other outlying islands, always at the bottom of the pay scale. CPNAB employed hundreds of Japanese American carpenters on Oahu – that is until December 7, 1941 – but the U. S. Navy specifically forbade workers of Japanese ethnicity from contract work of any kind on the outlying islands. As I write in Building for War, this was a rare nod to the underlying premise of the prewar Pacific defense contracts. The vast majority of CPNAB workers were white men from the mainland.

While the CPNAB projects on Guam, American Samoa, and at Cavite in the Philippines utilized local labor, Wake and the other remote atolls had been virtually uninhabited prior to the arrival of the contractors. At Midway, Wake, and Guam, where Pan American Airways had established stations in 1935, the airline employed natives of Guam (Chamorros) in a variety of positions. During 1941 the CPNAB executives debated bringing Filipino workers to Wake for unskilled labor, noting that they would “work cheap,” but acknowledging that there would be the “problem of mixing with whites.” In the end the mainland hiring offices continued to send a steady stream of white construction workers and Chinese Americans for camp labor to the Pacific.

On December 8, 1941, Pan American’s Guamanian employees on Wake Island numbered forty-five, ten of whom died in the initial Japanese bombing that destroyed the Pan American hotel on Peale. After the attack crews gutted the bullet-scarred Philippine Clipper of cargo and furniture to maximize the evacuation load. Passengers and American Pan Am employees were first on the list to evacuate and some of the contractor volunteers were offered a ride (all declined with “casual bravado”), but when two Chamorro stowaways were found on board, they were booted off. U. S. Navy Commander Winfield S. Cunningham later noted that this was an “unfortunate time to draw the color line.” The Guamanian Pan Am employees had no choice but to join the other civilians – some helping, some hiding – to face what would come on Wake Island in December 1941.

During the research and writing of Building for War, I relied on primary source documents for “real time” pictures of events and attitudes without the distortions of memory. I tried without success to find letters or diaries written by Chinese American contractors or Guamanian Pan American employees that might reveal their “real time” perspectives and experiences on Wake Island in 1941. The closest I could come was an interview that a family member did on my behalf with her father in 2009. Lana Lee interviewed her dad, Suey “Eddie” Lee, who was a young mess man from San Francisco on Wake in 1941. Lee stated that all in his Chinese American group worked as waiters in the mess hall, setting up the tables for dining, serving the food, and cleaning up afterwards. All of the “brown people,” he recalled, were housed in a separate barracks, though he felt they were treated fairly and did not experience discrimination. Lee’s memories of the attack and siege were similar to those of other survivors. At surrender, he recalled, all prisoners were stripped and made to sit together on the ground overnight. Lee remembered “leaning on a tall white prisoner’s back while sleeping.” There was no color line that night.

Too bad that’s what it took.

- Wake Mess Hall, 1941, National Archives

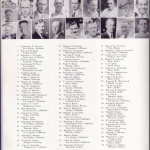

- New hires in Boise, 1941, Idaho Daily Statesman

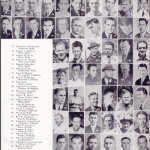

- Wake Island contractors, May 1941, National Archives

- Wake workers, 1941, photo courtesy of Guy McGee Family Collection

- Blue Book p. 34, URS Corp.

- Blue Book, p. 35, URS Corp.

My father arrived in San Francisco either 1938 or 1939 from China and didn’t speak much English. He sought work in Brawley, CA, and knew that there would be no future there because everyone spoke Spanish. When he was drafted and reported back to SF, he chose contract work, which paid a higher monthly salary than that of infantry. So, of course, he would be paid at “bottom scale” for someone who spoke little English and being a foreigner.

There were Japanese living in the USA who were loyal to the emperor of Japan and marched in parades in Berkeley, CA proclaiming their allegiance to the pagan sun emperor prior to Dec.7. In addition, after the Pearl Harbor bombing, there were American-born Japanese men who went to Japan and fought for that country and flew planes against our side. I heard all this from callers to the Barbara Simpson show on ksfo 560am radio. You can contact her at http://www.ksfo.com.

Segregation in the military is beneficial when it comes to actual combat, whereby certain ethnic races (either Mexicans or Navajo, I forgot which) become experienced in fighting the enemy and are able to teach and communicate to their same when a fresh group of soldiers arrive for replacement. This occurred during the Korean War where the new replacement of the same ethnicity were broken up and led to slaughtered due to desegregation orders. I think this topic was also on the Barbara Simpson radio show.

Enforced racial integration, preferential treatment, social equality lead to resentment and sabotage, as I figured what happened to our radio products, tv sets, and car industries during the 1960’s, as well as our schools and neighborhoods. (Besides, MLK was a plagiarist, an adulterer, and …. http://www.traditio.com Commentaries January 20, 2003).