Guam on the Front Line

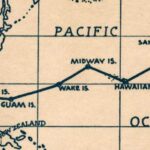

Pan American Airways had a strong connection to several of the Pacific islands where the U.S. Navy was building air bases on the eve of World War II. In Building for War, I discuss the mutually beneficial relationship that allowed the airline to establish bases on Midway, Wake, and Guam in 1935, and the Navy to follow up by building facilities on those strategically located islands a few years later. By late 1941 naval air stations were nearing completion on Midway and Wake, Marine detachments set up gun batteries, and Pan Am Clippers flew in and out as usual. Guam also had busy Clipper traffic, but no air station and no gun batteries: it was too close to Japan.

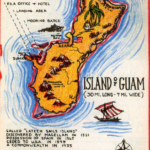

In 1935 Pan American Airways – optimistic of the Navy’s approval to build a chain of clipper bases eight thousand miles across the Pacific – had leased and loaded the SS North Haven, which steamed out of San Francisco Bay in late March. The expedition established the first Pacific base at Pearl City on Oahu, then worked its way west to carve out the Midway and Wake Island projects, leaving crews on those islands to continue the work (see my 2012 post on building Wake: Pan American), and then to Guam, another 1,500 miles west of Wake. The large, lush, well-populated island of Guam had been under control of the U.S. Navy since 1898, when it became a U.S. possession following the Spanish-American War.

When the North Haven arrived at Guam in May 1935, Pan Am expedition leader William Grooch first paid respects to the Naval Governor, Captain G. A. Alexander, who gave his enthusiastic support for the Pan Am plan. The governor offered the use of a long-vacant marine seaplane base at Sumay on Apra Harbor with hangar, shops, water, telephone service, and a new generator for electricity, and the Pan American Guam base quickly took shape – in contrast to the Wake and Midway stations that were literally built from scratch. A narrow, 900-foot-long walled slip to moorage would provide essential protection in the harbor, but the clipper wingspan would be a tight fit: the solution was to engineer a guide-rail trolley on each wall to secure the plane for safe passage through the slip.

In short time, the North Haven departed Guam for Manila in early June to take on drums of fuel and supplies for the new bases on the return trip. The Pan American Clipper was just that month making its first landing at Midway. Radio shacks linked Alameda, the new bases, and the clippers; direction finders aided clipper navigators to find the little dots on the Pacific map. In August 1935, a clipper made the first landing on the lagoon at Wake Island and, in October, on Apra Harbor at Guam. In December 1935, the China Clipper made its well-publicized first voyage carrying airmail on the full round trip to Manila and back. By October 1936, weekly clippers carried passengers who enjoyed overnight stays after each leg of the trip at Pan Am’s modern hotels with all the amenities, and the route extended to Hong Kong in the summer of 1937.

Most of those living on Guam or passing through in the late 1930s knew little of the drawn-out controversy that the island provoked among U. S. military and government branches. Military planners had for decades argued over Guam’s potential in future hostilities with Japan. In 1938 the Hepburn Board recommended the construction of naval bases across the Pacific, but Congress did not agree to fund the Guam project until 1940, and it did not get underway until the summer of 1941. J. H. Pomeroy and Co. of San Francisco – one of five construction companies in the CPNAB consortium – managed the Guam project. It included only some harbor development and military housing, but no naval air station or defensive installations. Guam did not even have an airstrip. Pomeroy established its construction base in Sumay near the Pan Am complex with about seventy American “key men” and scores of local Chamorro laborers. However, typhoons and shipping delays held up supplies through the fall, and the contractors were only able to make some progress on a breakwater in the harbor.

Meanwhile, Guam’s Pan Am employees had settled into a comfortable routine. Four days a week they moved into high gear preparing for the arrival of an east or westbound clipper. The Guam station monitored the inbound flight until the clipper settled on the buoy-marked channel in Apra Harbor and maneuvered into the slip to moor at the pier. Attendants whisked international passengers to the 20-room hotel for their overnight stay, and the ground crew unloaded cargo and serviced the plane for its morning departure. Navy and Marine officers and local businessmen often joined the visitors for cocktails in the evenings as twilight descended over the peaceful compound.

The veneer of peace still held strong on Guam, despite the war news, the Navy’s recent evacuation of all non-local American dependents (women and children), and the noticeable drone of high-altitude Japanese aircraft circling over the island. Guam’s proximity to Japan and its fortified mandates in the Marianas just to the north virtually ensured that if Pacific tensions reached the boiling point, unfortified Guam would be an easy target. Nevertheless, most Americans trusted that the mighty U.S. Navy would quickly come to their rescue.

Before dawn on December 8, 1941 (December 7 in Hawaii), the Guam station manager delivered a favorable weather forecast for the scheduled Philippine Clipper from Wake Island. Shortly after came the stunning news of the Pearl Harbor attack and the westbound clipper aborted its flight, returning to Wake. Within minutes of the news reaching Guam, the roar of Japanese bombers from nearby Saipan confirmed their worst fears. Among the first targets was the Pan American complex where bombers struck the hotel, crew quarters, and fuel tanks, killing two kitchen workers. Waves of attackers swept over the island for hours before flying off. As the day went on Japanese squadrons returned to wreak havoc as residents cowered or fled to the jungle; Pan Am employees and civilian contractors pooled food and supplies and headed for the hills.

The air attacks continued through December 9th as all waited in vain for the American rescue: Japanese troop transports and warships were already on the way. That night the Marines of the Insular Patrol and the native Insular Force and a few other navy men – less than one hundred, insufficiently armed men – took up position to defend the seat of government in Agana, but in the early morning hours Japanese ships landed, disgorging nearly six thousand troops who quickly overcame all resistance. The island surrendered at 7 am, December 10, 1941. Japanese forces rounded up people as they emerged from the steaming jungles. Within a month all hopes of a U. S. Navy rescue had evaporated: Guam braced for a long occupation, and the victors shipped the surviving American military and civilian prisoners to Japan for the duration of the war. The U.S. would retake Guam in 1944 and turn it into a powerful fortress against Japan in the last year of war, but the sacrifice at the beginning would not be forgotten.

- PAA Pacific map Pan American Historical Foundation

- PAA Guam Map Carol Nay, “Timmy Rides the China Clipper,” (Chicago, 1939)

- PAA Apra Harbor, Guam Don Farrell, Naval Historical Center

- PAA Guam compound R.O.D. Sullivan, Pan American Historical Foundation

- PAA Hotel Guam Micronesian Area Research Center, Guampedia

- Pan Am Guam hotel plaque, courtesy Iain Currie, 2025