Draw It, 1941

Drawings may look simple on the surface, but they convey complex messages about both the subject and the person making the drawing. During my research for Building for War I encountered many line drawings from 1941: some were professional and purposeful, others were personal sketches found in letters and diaries. I found them as revealing as the written primary sources on which I based much of the book, but only one made it into the published book (a map of Wake, sketched by my grandfather in a letter. The Wake maps are fascinating and occupy a category of their own, subject for a future post).

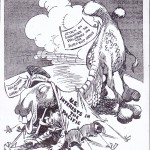

Among my earliest research targets were old newspapers. I squinted through reels and reels of microfiche from the Boise, Spokane, and Portland papers, culling relevant articles, photographs, and political cartoons. I found the cartoons especially revealing of the prevailing American attitude toward the Japanese – at once demeaning and cautionary – and include two here from the Idaho Daily Statesman. Drawn in the immediate context of unfolding prewar events, they speak volumes.

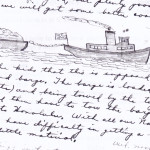

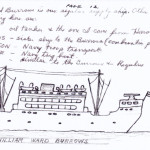

Many a lonesome Wake worker sketched pictures in his letters home. Some tried their hands at maps of the admittedly simple outline of the atoll or a drawing of a building under construction or visiting ship (until they were warned against it for security reasons). Peter W. Hansen, a carpenter from California, wrote long and often to his wife and three children at home, and included sketches of the barracks he was building, the big globe and their relative positions on it (too far away!), and other images. Hansen sketched the USS William Ward Burrows that frequently brought workers and supplies to Wake and a sturdy tug towing a barge – a common sight at Wake in 1941.

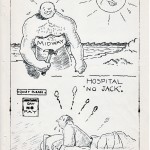

The Battle of Midway in June 1942 turned the tide for the United States in the Pacific and Midway will always carry that banner, but before the famous battle it was just another outlying Pacific Island being fortified for war. Like Wake in 1941, Midway was a CPNAB project where a naval air station was taking shape and a Pan American station hosted transpacific Clippers (the prefabricated PAA hotels on Wake and Midway were mirror images). Morrison-Knudsen Company held primary sponsorship of both projects for CPNAB and shared plans and men between them. A friendly rivalry prevailed between the two projects, often played out in their newsletters. The unrelenting sun, as a company poster warned on Midway, posed the same danger of sunburn as it did on Wake.

In the fall of 1941, the president of Morrison-Knudsen, Harry Morrison, and his wife Ann paid a visit to Wake, during which they were grounded longer than their planned week-long stay by bad weather. As was her habit, Ann wrote in her diary during the trip, describing the events of the days and her thoughts. She wrote about the startling experience of crossing the International Date Line on the Pan American Clipper en route to Wake and later how she endured the storms, visited with the “Boise boys,” and about the Chinese American houseman in the Wake guest house who admonished her for listening to Japanese broadcasts on the radio. Back home by the time the war started, Ann and Harry Morrison lamented the fate of the Wake men with whom they had just been. Within a year, the new Morrison-Knudsen company magazine began carrying excerpts of Ann’s diary, complete with illustrations, and the full diary was published as a book after the war.

My final selection comes from Joseph J. Astarita, one of the Wake survivors, in his Sketches of P.O.W. Life published by Rollo Press in 1947. Astarita explains in the introduction that he made these drawings during the “freezing winters, without heat, and the stench of China summers” as he and his fellow Wake prisoners endured three years and eight months of captivity. He drew on any kind of paper he could find and concealed the drawings rolled up in empty Red Cross shaving cream tubes where they passed safely through many a “shakedown” by prison guards in both China and Japan. The majority of the forty drawings in his published book reflect the POW experiences, including caricatures of the Japanese guards, but I selected a drawing Astarita would have made from memory of damage during the siege on Wake in December 1941. I could not bend more than once the spine of the tan book that he gave my father decades ago when they were free men again.

Some pictures may only be worth a couple hundred words, not a thousand, but all carry the flash of a singular moment in time and for that they are priceless.

- Idaho Daily Statesman, August 1, 1941

- Idaho Daily Statesman, October 9, 1941

- Peter Hansen Family Collection

- Peter Hansen Family Collection

- M-K Records, URS Corp.

- The Em-Kayan, February 1946

- The Em-Kayan, March 1946

- Joseph Astarita @1947