JPAC Wake Island Mission

In 2011, a worker discovered a group of human remains exposed on the north beach of Wake Island near the site where American POWs were massacred in October 1943. The Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) sent a team to Wake to recover the remains and excavate the site. JPAC opened a mission to identify the remains and I volunteered to locate families of the “Wake 98” to provide DNA reference samples to aid in identification. While the majority of the massacre victims’ remains are interred in the mass grave in Punchbowl Cemetery, none were ever positively identified, so the mission had to cover all 98. This week I submitted my final report to JPAC. In the course of three years I discovered that the 98 left far more than their bones behind: they were sons and brothers, fathers and husbands, uncles and cousins, whose deeper identities are found in the reawakened memories of their families.

In 2011, a worker discovered a group of human remains exposed on the north beach of Wake Island near the site where American POWs were massacred in October 1943. The Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) sent a team to Wake to recover the remains and excavate the site. JPAC opened a mission to identify the remains and I volunteered to locate families of the “Wake 98” to provide DNA reference samples to aid in identification. While the majority of the massacre victims’ remains are interred in the mass grave in Punchbowl Cemetery, none were ever positively identified, so the mission had to cover all 98. This week I submitted my final report to JPAC. In the course of three years I discovered that the 98 left far more than their bones behind: they were sons and brothers, fathers and husbands, uncles and cousins, whose deeper identities are found in the reawakened memories of their families.

To date we have located all but nine families of the ninety-eight Americans killed on Wake Island in 1943. Seventy-five families have provided DNA reference samples, but I had to suspend a total of twenty-three cases. It was difficult to let go of the fourteen cases where I found family lines and made contacts, but where we could not locate a donor or, sadder still, where there were just no qualified living donors left in the extended family. I was deeply frustrated that, despite all of the genealogical and research tools available, I could find no trace of nine families. In some cases the individual was a recent immigrant; others may have been deliberately “shallow-rooted,” leaving no trail for a reason.

Dead ends happen, but if there is a lesson here, it’s that we all need to get our DNA on the record. Mitochondrial DNA passes through the maternal line down generations. Y-chromosome DNA follows the paternal male line; children carry the nuclear DNA of their parents. It is just a little bit of spit, folks. Since the human genome was first sequenced in 2000, our understanding and applications of DNA have increased dramatically. In her new book The Invisible History of the Human Race, Christine Kennedy argues that DNA can “open up tracts of human history that had been entirely obscure.” From microscopic lab analysis to the broad lens of history, DNA is the tool of our time.

As far as I know to this date, JPAC has made no positive identifications of the Wake Island remains. We will continue to honor all of our WWII Wake dead at the mass grave in Punchbowl Cemetery in Hawaii, where the comingled remains were laid to rest. A large bronze plaque lists the names of 176 military and civilian casualties, including all of the Wake 98. Several Wake Island casualties are buried independently and not named on the mass grave plaque. Medal of Honor recipient Henry Elrod is interred in Arlington National Cemetery; a few other individuals were buried separately in Punchbowl Cemetery.

Another name missing from the mass grave plaque is that of Wildcat pilot Lt. Carl R. Davidson, who was shot down in aerial combat over Wake on December 22, 1941. Davidson is one of the 83,000 MIA that JPAC is tasked with “bringing home.” Those are the missing in action or unaccounted for from WWII, the Vietnam War, Cold War, Korean War, and Persian Gulf War. About 50,000 of that number are lost at sea and it is hard to imagine what future technology could ever enable recovery of human remains from the Pacific Ocean floor. It’s daunting enough to search decades-old battlegrounds, wreck sites, and unmarked graves in remote locations, but consider what it would take to probe the briny deep, layered with countless generations of marine detritus. Recently, the Department of Defense’s Inspector General called for a realistic prioritization of the total and establishment of criteria to determine “non-recoverable” status, but that remains to be done.

Despite the irrationality of the big picture, the immediate challenge is to accomplish the doable missions in a timely and efficient manner. Across the nation families of the MIA have organized and lobbied for stepped-up recovery missions and accountability. In 2010, Congress amended Title 10, the Missing Persons Act, and issued a mandate increasing the number of MIA identifications per year to two hundred by fiscal year 2015. The Department of Defense reorganization of JPAC, the Defense POW-Missing Personnel Office (DMPO) and the military’s Central Identification Lab (CIL) at Dover AFB is underway now with a target date of January 1, 2016. The reorganization is intended to make the overall mission more functional, accountable, streamlined, and thus able to more than double its current annual identifications as required by Congressional mandate. This isn’t headline news, but there are numerous sides to this unfolding story and American citizens would do well to follow it.

It has been my honor to work with JPAC and the Central Identification Lab on the Wake Island Mission. I am grateful to the families of the 98 for their openness and cooperation. Even when families lose any hope that their loved one lived on, the absence of physical proof of death leaves a hole that can’t quite be closed. May the Wake 98, wherever their bones are, rest in peace.

See my blog archive for past posts on the JPAC mission and the Wake 98. For queries on submitted or suspended cases or for additional information, please contact me.

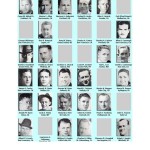

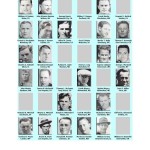

Gallery photo sheets courtesy John K6MM, K9W Wake Atoll 2013: Commemorative DXpedition. The source for these prewar photos, many of which I have posted previously, is the “Blue Book,” aka A Report to Returned CPNAB Prisoner of War Heroes and their Dependents (Boise, ID, 1945)

Bonnie: Many thanks for the effort that it must take to write these blogs. I really enjoy reading them. I looked carefully at each picture of the 98 shown and cannot understand why Hettick in Visalia did not respond. I truly appreciate what the men and women of all the wars up to now have sacrificed for our freedom. Each book I read adds to my feelings.

gary